The Horticulture Movement romanticized farming while neglecting farmers, but there is not much romance in farming. There is an ethos to the love of the land; ownership and back-breaking toil, the business of creating and distributing crops; an embodied knowledge of the climate, soil, and growing seasons; arthritis, lung diseases, broken bones; passing the work down to the next generation; infant mortality; fecundity and growing, death and dying. The re-presentation of romantic imagery in art and the orderly practice of dominance and control of Nature through landscape architecture ignored the reality of the land and the people who toiled on it.

That conflicted morality is still informing our present.

From the rise of the Industrial Elite and the Horticultural Movement to Civil War

The Moral Dimensions of Horticulture in Antebellum America

The horticulture vogue was simultaneous with the condemnation of Americans, by evangelical preachers and highbrow European travelers alike, as a people absorbed in a feverish pursuit of material gain. Materialism threatened American society at its foundation, for its success depended on its citizens' ability to place good before private benefit. Materialism was also blamed for fostering a culturally narrow and coarse society, one where there was no appreciation of beauty or art. A lack of interest in horticulture, then, represented the failure and the proof of America's cultural inferiority.

Between the Revolution and the Civil War, many of Boston's elite settled on country estates, took up gentleman farming, and made a stab at horticultural experimentation. Even more identified themselves with what contemporaries termed "rural pursuits"

One cornerstone of this ethos was the high value placed on such entrepreneurial traits as frugality, industry, sobriety, and personal simplicity. These were likely to make a man rich, of course, but they were also valued as ends in themselves, properly republican and a refreshing contrast to the decadence that characterized many members of Old World elites.

One must have riches, but more important, one must rise above them, valuing them only for the good they can do in this world.

Cultivating Gentlemen

The Meaning of

Country Life among the

Boston Elite

1785-1860

Tamara Plakins Thornton

Anna Rubin, Director of External Relations, Fairbanks Museum & Planetarium

Through all the currents of social agitation of the early nineteenth century appeared a constant reiteration of a belief in the nearness of a millennial society. The vision of a free man inhabiting a free world has engaged the attention of aspiring souls in all ages and climes. The back country of early America, stretching from interior New England across New York State and into the Ohio Valley, gave birth to numerous prophets and messiahs who aimed at being the architects and builders of a new social order. ..

The spread of a belief in evolution and the espousal of the scientific attitude profoundly affected the course of theology. To a large degree the new outlook undermined the basis of revivalism, that mainspring of so many reform movements of the early years of the century. The vision of the millennium faded.

SOCIAL FERMENT IN VERMONT

1 7 9 1 - 1 8 5 0

BY DAVID M. LUDLUM

Columbia University Press, 1939

As the desire to bring nature into the cities and into the public sphere surged, so too did the desire to have a private, isolated green space away from everything and everyone. When the middle class could enjoy public gardens, some elites retreated to their own gated garden spaces to escape the masses. All over the country individuals with wealth began to build large private gardens, and many of them focused not only on large open spaces, but also on unique areas with ornamental plants to add color to the green landscape. Although the styles of these gardens varied from area to area, and designer to designer, many of these gardens included many different exotic plant species from all over the world. It was in the creation of these private gardens that the botanical industry grew to exponential heights.

Trina Gay, landscape designer

Barbara Paulson, master gardener, Morrill Homestead

Smithsonian Gardens

A Timeline of American Garden History

Continue your immersive experience here

(click on the arrow)

“Circumstances don't make the man, they only reveal him to himself.”

― Epictetus

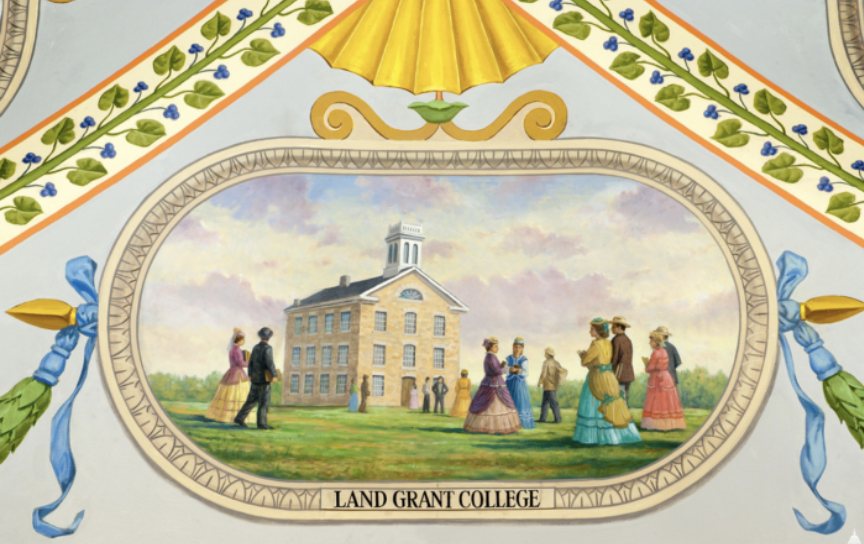

But just occasionally, the man makes the circumstances. Such is the case with Justin Morrill. With the backdrop of a changing Vermont – from frontier to republic, from republic to state, Vermonters always seem to “show up” when the American Experiment needs them most. It’s town meeting tradition, rugged landscape, and hard-working agricultural life have nurtured brilliant minds in the service of “Freedom and Unity.” Morrill’s signature work, the passing of the Land Grant Act and the establishment of universities of agricultural research, experimentation, sustainability, and diversity, was neither his idea nor without controversy, but it is his legacy.

“It is not enough that we have an immense territory or an immense population, but every acre and every man, where nature has been equally bountiful, should be the equal in productive power of any other acre or any other man. It is not enough that, with a population of nearly fifty million, only about twenty-five thousand students annually find their way through any and all of the old literary colleges. It seems obvious that both colleges and common schools require the earnest attention and the most precious resources of all the States, as well as of the General Government. Without undertaking the entire control of the general subject, Congress may yet legitimately make a contribution so emphatic that no State will falter in generous cooperation. The light of the nation, as that of the sun among planetary states, should break forth as the greater morning light to rule the day.”

At the intersection of science and good governing, Morril’s work continues to supports solutions to existential threats. Not unlike the Antebellum period, where the accumulation of tremendous wealth threatens our foundational principles in the service of material greed, we hear the drumbeat of emancipatory inquiry in the service of a community tied to the land that sustains us.